Daisy Bacon

Daisy Bacon | |

|---|---|

.jpg/220px-Daisy_Bacon_in_bed_(cropped).jpg) Bacon, from a 1942 publication | |

| Born | Daisy Sarah Bacon May 23, 1898 |

| Died | March 1, 1986 (aged 87) |

| Occupation(s) | Magazine editor, writer |

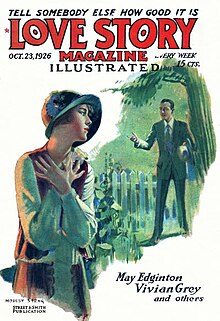

| Known for | Editor, Love Story Magazine (1928–1947) |

Daisy Sarah Bacon (May 23, 1898 – March 1, 1986) was an American pulp fiction magazine editor and writer who was best known as the editor of Love Story Magazine from 1928 to 1947. She moved to New York in 1917, working at several jobs before being hired in 1926 by Street & Smith, a major pulp magazine publisher, to assist with "Friends in Need", an advice column in Love Story Magazine. Two years later she was promoted to editor of the magazine, and stayed in that role for nearly twenty years. Love Story was one of the most successful pulp magazines, and Bacon was frequently interviewed about her role and her opinions of modern romance. Some interviews commented on the contrast between her personal life as a single woman, and the romance in the stories she edited; she did not reveal in these interviews that she had a long affair with a married man, Henry Miller, whose wife was the writer Alice Duer Miller.

Street & Smith gave Bacon other magazines to edit: Ainslee's in the mid-1930s and Pocket Love in the late 1930s; neither lasted until 1940. In 1940 she took over as editor of Romantic Range, which featured love stories set in the American West, and the following year she was also given the editorship of Detective Story. Romantic Range and Love Story ceased publication in 1947, but in 1948 she became the editor of both The Shadow and Doc Savage, two of Street & Smith's hero pulps. However, Street & Smith shut down all their pulps the following April, and she was let go.

In 1954 she published a book, Love Story Writer, about writing romance stories. She wrote a romance novel of her own in the 1930s but could not get it published, and in the 1950s, also worked on a novel set in the publishing industry. She struggled with depression and alcoholism for much of her life and attempted suicide at least once. After she died, a scholarship fund was established in her name.

Early life and early career[edit]

Daisy Sarah Bacon was born on May 23, 1898, in Union City, Pennsylvania. Her father, Elmer Ellsworth Bacon, divorced his first wife in 1895 to marry Daisy's mother, Jessie Holbrook. Elmer died of Bright's disease on January 1, 1900, and Jessie moved to her family's farm in Barcelona, New York, on Lake Erie on the outskirts of Westfield. Daisy was taught to read and write at age three by her maternal grandmother, Sarah Ann Holbrook.[1] One of Daisy's great-uncles, Dr. Almon C. Bacon, was the founder of Bacone College in Oklahoma.[2]

Jessie remarried in 1906, to George Ford. George and Jessie had one child, Esther Joa Ford, born October 1, 1906; George died on January 24, 1907, leaving Jessie Ford alone to raise the two half-sisters.[1] In 1909 Jessie left the farm and moved into Westfield, where Daisy attended the local high school, Westfield Academy. While she was in high school the Westfield Republican published an essay she wrote about the Louisiana Purchase for a competition. She graduated from high school in 1917 as valedictorian, and was awarded a $100 scholarship to Barnard College, though she never enrolled there.[3] Shortly after Daisy's graduation from high school, the family moved to New York City, living in a hotel at first.[4]

Bacon worked at several different jobs when she first moved to New York. She was briefly a photographer's model, before taking a job at the Harry Livingston Auction Company, which sold unclaimed luggage left at hotels by guests. She collected and recorded the auction payments.[5] Bacon also wrote and submitted articles and fiction to the magazines of the day, but she was not immediately successful in selling her work.[6]

In the early 1920s Bacon sold two articles to The Saturday Evening Post: one about her work at the auction company, and a ghost-written account of the life of a chambermaid in a New York hotel, titled "On the Fourteenth Floor".[7] Years later Bacon's half-sister Esther recalled living at the Astor Hotel and becoming friends with Arturo Toscanini's wife, Carla, and it is possible that Jessie took a job as a chambermaid at the Astor, with room and board, during the family's first years in the city.[8]

Street & Smith[edit]

Bacon continued writing, without further success, later recalling that she "worked like slaves to get into Liberty and never made it".[9] In March 1926 she was hired by Street & Smith, one of the major pulp magazine publishers, as a reader for "Friend in Need", an advice column that ran in Love Story Magazine.[10] The magazine had been launched as a monthly in 1921, and was successful enough to switch to weekly publication in September 1922.[11] The advice column received about 75 to 150 letters a day, mostly from women, and between ten and twenty were printed each week. Another Street & Smith employee, Alice Tabor, also worked on the column. Street & Smith insisted that no matter what the letter-writer's problem might be, divorce (which was scandalous at the time) could never be recommended as a solution. The letters covered every kind of romantic and matrimonial problem, and Bacon's biographer, Laurie Powers, suggests that the letters "gave Daisy a priceless education in the magazine's audience ... [and] became the foundation of Daisy's uncanny ability to know what her readers wanted to read in a romance".[12] While working on "Friend in Need", Bacon also wrote fiction for Love Story, beginning with "The Remembered Fragance".[13]

Editor of Love Story Magazine[edit]

In March 1928 Ruth Abeling, the editor of Love Story, was fired, and Bacon was made editor in her stead.[14] She hired her sister Esther as her assistant; to ensure that their relationship appeared professional at the office, the two of them switched to using their last names, Bacon and Ford, for each other, both in and out of the office.[15] Bacon found she had to adapt her usual soft-spoken and rather genteel speech to be successful in some of her working relationships at Street & Smith: "well-bred tones did not spell authority to them", she later recalled, but "after I learned to talk to them in language which I had heard my grandfather's stable boys use, everything was fine".[16]

There were so many stories submitted to the magazine that other staff had to be employed to reduce the volume of submissions that reached Bacon's desk to a manageable quantity; even so Bacon found herself reading about a million words of manuscripts each week.[17] The fiction in the magazine when Bacon began working at Street & Smith was Victorian in tone,[18] and Bacon was scornful of the characterization: "The heroines were usually paid companions, governesses, or employed in some such genteel occupation and were always so sweet that it made you want to choke them!"[13] She wanted the heroines of her stories to more closely resemble her readership, working as secretaries or beauticians. However, she also understood the role of glamor in the magazine: readers liked to read about chorus girls and models struggling to succeed, and about women in unusual roles such as pilots.[19] A common stereotype in romance fiction was a poor girl with rich relatives who cruelly mistreated her; Bacon argued that "anyone who thinks that only those people who do not have to work for a living have the capacity for making other people's lives miserable has just never spent an hour inside of the average factory, hotel, school, or department store or around almost any office."[20]

Circulation was strong at the time Bacon became editor, at perhaps 400,000, a very high figure for a pulp magazine.[21][22] The magazine continued to prosper in her hands, and the circulation may have reached 600,000.[23][note 1] In her first year as editor, Bacon was forced to write the ending to a serial by Ruby Ayres. The serial had already begun when Bacon took over as editor, even though Ayres had not sent the last installment by the time the first one appeared in print. When the final installment did not arrive in time for publication, Bacon delayed the problem for a week by splitting the most recent episode into two, but by the time the deadline for the next issue came, the rest of the manuscript still had not arrived. The story was about an unpleasant woman whose husband was falling in love with his secretary. In Bacon's version the wife falls from a high window and dies, leaving him free to marry his secretary. Bacon was criticized for the ending, but Ayre's own version of the installment, which finally arrived, had the wife die in the same way.[25][26]

Bacon became friends with some of her writers, inviting them to her apartment and buying them lunch. Douglas Hilliker, an artist who drew interior illustrations and later painted magazine cover art, lodged with Bacon and her mother and half-sister for a while in 1930, along with his wife and daughter. Bacon was friends with Maysie Grieg, who was already a successful writer when Bacon met her, and with Gertrude Schalk, an African-American writer who sold her first story to Bacon in 1930.[27] Bacon and Schalk planned an unusual book together: a collection of Schalk's stories that would have included the initial version submitted to Bacon, the correspondence over the changes Bacon requested, and the final version printed in the magazine. The project had to be abandoned when Schalk's manuscripts were accidentally destroyed and Bacon's correspondence files were lost in an office move.[28][29]

In mid-1934, Street & Smith decided to resurrect Ainslee's Magazine, which had been merged into Far West Illustrated in 1926, as another love story magazine.[30] It was titled Ainslee's, and given to Bacon to edit from its first issue, dated December 1934.[30][31] It was in bedsheet format, with slightly more risqué plots, and an occasional mention of nudity. Powers comments on the language used: "More explicit kissing scenes used word such as 'sensuous' and 'intimate' [and] the word 'damned' showed up several times."[32]

In 1935 Bacon submitted a manuscript of a romance novel to William Morrow. It was rejected, and she seems not to have submitted it elsewhere.[33]

Late 1930s[edit]

Bacon became aware that there was a glass ceiling in effect for women at Street & Smith, and that there was a limit to how high she could progress in the company.[34] In late 1936 an article of hers titled "Women Among Men" appeared in an early issue of The New York Woman; it was published anonymously, presumably because she was concerned about how Street & Smith's management would react to it.[35] Among other complaints she described how her business ideas were treated differently from those of the men in the office: "Over a period of years I've had a great many ideas about promoting new business but they have never been taken up. And not only that but several have been accepted later when they were put forward by men. Two of the best plans I ever had ... have been recently accepted and put into operation by men who are ... almost totally without business experience."[36] Bacon's anonymity did not last; interest in the article was enough to generate gossip about who the author might be, and in December she was identified as the author in Walter Winchell's newspaper column. She later recorded that she showed up at the office that day unaware of Winchell's piece, and was "blissfully unaware that everyone in the office was lying in wait for me".[37]

In 1937 Street & Smith gave Bacon Pocket Love to edit. This was a new magazine, probably started in an attempt to acquire part of the increasing market for paperbacks and digest-sized magazines. It only lasted for four issues.[38] Ainslee's had been retitled Smart Stories, and under Bacon's editorship it lasted until 1938.[39] The death of George Campbell Smith, Jr., in April 1937 led a year later to the arrival of Allen L. Grammer, from Curtis Publishing, to manage the company. Grammer brought several of his staff with him, and quickly began making sweeping changes to improve the efficiency of Street & Smith's business.[40]

1940s and the end of the pulps[edit]

In July 1940, Grammer made Bacon editor of Romantic Range, a Western romance pulp, and the following year Grammer also gave her Detective Story to edit.[39] The Special Services Division planned to distribute copies of Detective Story to men in the armed services overseas, and as the editor, Bacon temporarily became their part-time employee.[42]

Bacon was frequently interviewed, in newspapers and at least once on the radio, while working at Street & Smith.[43] On romance in mid-twentieth century America, she commented in 1941 that "It is better for girls to acquire careers first, husbands afterward," and "financial independence for the wife is an ideal basis for marriage. To be singled out by a girl with a good job is the highest form of flattery for a man. She does not need his support. Therefore she loves him for himself."[44] A 1942 profile said "In her pages, she offers to the average woman—not a flight from actual life—but a heightened reality." The same profile quoted Love Story's circulation as between two and three million readers a month.[45] Another estimate from 1941 gives 350,000 as the weekly circulation, but even this lower figure was still much higher than most pulp magazines.[46][22] Another theme in her interviews was that she was the editor of a magazine about romance, but was herself unmarried: a 1941 article was titled "Editor Sells Romance to Lonely Wives, but Has No Love Herself",[47] and another interview the same year was titled "Cobbler's Child".[43][note 2]

Street & Smith published annual anthologies of stories from their magazines, and in the early 1940s Bacon and Ford were given responsibility for producing these. All-Fiction Stories drew its contents from all Street & Smith's fiction magazines, and there were also specialized titles, though these did not necessarily appear each year. These included Detective Story Annual, All-Fiction Detective Stories, and on two occasions an annual drawn from Love Story.[49]

In late 1946 Grammer decided to cease publication of both Romantic Range and Love Story;[49] the last issue of each appeared in January and February 1947, respectively.[49][50] This left Bacon in charge only of Detective Story, but in June 1948 Street & Smith fired William de Grouchy, the editor of The Shadow, and Doc Savage, and gave them to Bacon to edit as well. These were both hero pulps, meaning that they carried a lead novel in every issue about the same character, whose name gave each magazine its title. The Shadow was a crime fighter, and Doc Savage was a scientific genius; the Shadow's novels were mysteries, and Doc Savage's varied between adventure, mystery, and science fiction.[51] Bacon converted both magazines from digest size to their original larger pulp format,[52] and later claimed that this had immediately led to a 25 percent increase in circulation for The Shadow.[51] She told Walter Gibson, who wrote the lead novels for The Shadow, not to change his approach to the fiction, but asked Lester Dent, the lead writer for Doc Savage, to return to the adventure format mixed with science fiction elements that had characterized the early issues of the magazine. Dent was unwilling but produced three short novels along the lines she requested. Bacon rejected one of Dent's manuscripts, and as there was no time for Dent to write a replacement novel, an issue of Doc Savage had to be skipped.[52] Bacon also rejected multiple plot suggestions from Dent, and pulp historian Will Murray describes the relationship between Bacon and Dent as "the most difficult writer/editor relationship Dent ever enjoyed".[53] According to Dent's wife, Dent "believed that a woman had no place editing an adventure magazine".[53] Bacon only had a short time to work on the magazines, however: in April 1949 Street & Smith announced that they were ceasing publication of all their pulp fiction magazines.[54] Bacon was let go and Ford was given the task of managing the production of the last issues of each magazine, that summer.[55]

Personal life[edit]

On July 10 of either 1922 or 1923, Bacon met Henry Wise Miller, the husband of Alice Duer Miller. The Millers were part of the Algonquin Round Table social group, but it was Alice who was the successful writer; Henry became a stockbroker, funded by his wife's money. The Millers lived somewhat separate lives, deliberately spending part of each year away from each other, and Powers comments that it is possible it was an open marriage.[56] Bacon and Henry Miller soon began a relationship.[57] She also began to suffer from depression during the mid-1920s.[58]

In 1929 Bacon and Miller spent two weeks together in England and France, just before the Wall Street crash in October.[59] A rift between the two at the end of the year was quickly healed, and since Alice Miller was often away in Hollywood or overseas, Bacon spent many weekends with Henry at Botts, Henry's house near Kinnelon in New Jersey.[60] In 1931 Bacon rented a house in Morris Plains, New Jersey, with plans to write a novel there. She often took Esther and her mother with her; the other two would frequently be left to themselves as Miller would come to pick her up and take her to Botts.[61] It is not known if Alice Miller was aware of her husband's infidelity, but she may have been. Powers suggests that her long poem Forsaking All Others (1931) is a veiled reference to her own marriage: the protagonist has an affair with a younger woman, but refuses to leave his wife for her.[62] Bacon's occasional problems with depression surfaced at times when she was at Botts, and Powers suggests that this might have been because the place reminded her of Alice's existence.[63]

Bacon's mother died in 1936, and Bacon's journals from that time start to record that she was aware she was drinking too much. The habit probably started during Prohibition, and in early 1937 Ford's journals began to include a symbol on some days that almost certainly meant Bacon had been drunk that day.[64][note 3] The notation appeared every few weeks, sometimes for several consecutive days.[34]

Bacon's relationship with Miller was beginning to show signs of fraying by the late 1930s,[65] and she also felt under pressure because of the change in management at Street & Smith in 1938.[40] In late May 1938 Bacon attempted suicide. A doctor visited the house, and three days later Bacon was admitted to Doctor's Hospital in Manhattan, staying there for ten days.[66]

Alice Miller died in August 1942. Bacon and Henry Miller's relationship was over by that time, though they still saw each other.[67] Bacon was probably seeing other men by 1942: photographs of her from that time include two of her with another man. Henry remarried in 1947, to Audrey Frazier, a college professor.[68]

Retirement[edit]

Bacon was initially happy in retirement; she bought a house in Port Washington, on Long Island, and planned to write a novel, "a scandalous tell-all" about publishing, to be titled Love Story Diary.[69] By 1951 her depression was causing her problems again, and although she was no longer drinking she was still concerned enough about alcoholism to clip articles about it for her journal. In May a long gap in her journal probably indicates another suicide attempt. She recovered physically, but by June she was "tearing out chunks of her hair", according to Powers.[70] She mostly gave up work on the novel after this for a while, eventually returning to it in 1952, and then decided instead to write a non-fiction book about how to write romance stories. The result was Love Story Writer, which was published in late 1954.[71] In 1963 Bacon started an imprint, Gemini Books, to reprint it, this time under the title Love Story Editor.[72] She never finished working on Love Story Diary; it was never published, and the manuscript was lost.[72]

Ford's husband died in 1962. Ford moved in with Bacon, and the two women lived together for the rest of Bacon's life. By 1981 Bacon was bedbound upstairs, and as Ford could not climb the stairs, the two women did not see each other for the last five years of Bacon's life. Bacon died on March 25, 1986, and was buried in Port Washington;[73] Ford died three years later.[74] Bacon and Ford planned a scholarship fund for journalism students from Port Washington High School, which was eventually established as the Daisy Bacon Scholarship Fund in 1991.[73][75] In 2016 the Baxter Estates Village Hall in Port Washington held an exhibit about Bacon, including her desk, photographs, manuscripts, and typewriter.[76]

Magazines edited[edit]

Bacon edited the following magazines while at Street & Smith:

- Love Story Magazine. Early 1928 to February 1947.[77][note 4]

- Ainslee's, also titled Ainslee's Smart Love Stories and Smart Love Stories during its run. December 1934 to August 1938.[78][79]

- Pocket Love Magazine. May to November 1937.[80][81]

- Romantic Range. Mid-1940 to January 1947.[82][83]

- Detective Story Magazine. Mid-1942 to Summer 1949.[84][85]

- Doc Savage. Winter 1949 to Summer 1949.[86]

- The Shadow. Fall 1948 to Summer 1949.[87]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The figure of 600,000 appears in a 1938 article about the industry, and appears in multiple modern sources, but according to Powers there is no documentation for this number. Editors at Street & Smith were not typically told the circulation figures for their titles, though Powers suggests it is possible Bacon did obtain the number from her management and became the source for the circulation figure.[24]

- ^ The reference is to the proverb "The cobbler's children go barefoot".[48]

- ^ The symbol was the shorthand notation for "tight".[64]

- ^ Bacon took over in March 1928, but Powers does not give the date of the first issue she was responsible for.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 15–20.

- ^ Adelaide Kerr, "Tough Editor: Daisy Bacon Brings Love to the Lonesome" Archived October 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Portsmouth Daily Times (July 10, 1941): 6. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 20–22.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 22, 25.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 26, 29–30.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 25.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 31.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 40, 43.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 47–49.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 55.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 58.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 63.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 61.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 44.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 65.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 82.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 67.

- ^ a b Hulse (2013), pp. 287.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 4.

- ^ Bacon (1954), p. 83.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 70–71.

- ^ Bacon (1954), pp. 149–152.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 80.

- ^ Bacon (1954), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hefner (2021), pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 110.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (May 14, 2023). "Index by Magazine Issue: Page 659". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Powers (2019), p. 111.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 113.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 118–119.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 119–123.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 120–121.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 121–123.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp.124, 128.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 140.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 128–129.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 149–150.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 148.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 139–144.

- ^ Daisy Bacon, "Combining Romance with Realism" Archived October 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The Philadelphia Inquirer (March 9, 1941): 106. via Newspapers.com

- ^ "Love Story Editor" Archived October 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Detroit Free Press (September 27, 1942): 2. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 139.

- ^ Kerr, Adelaide (March 20, 1941). "Daisy Bacon Editor Sells Romance to Lonely Wives". Press and Sun-Bulletin. Binghamton, New York. p. 28. Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Stone (2006), p. 69.

- ^ a b c Powers (2019), p. 159.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (May 27, 2023). "Romance/Romantic Range". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 162.

- ^ a b Murray (2012), p. 48.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 162–164.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 165.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 166.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 26–28.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 25–30.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 29.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 74–76.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 77–78, 86.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 87.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 132.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 142, 151.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 149, 159.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 170–171.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 171–174.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), p. 177.

- ^ a b Powers (2019), pp. 177–180.

- ^ Powers (2019), p. 180.

- ^ Salazar, Farrah (December 5, 2019). "Port Washington's Very Own Queen of the Pulps". Port Washington News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ Powers, Laurie (March 23, 2016). "Daisy Bacon on Exhibit". Laurie's Wild West. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 58, 159.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 110, 132.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (June 12, 2023). "Index by Magazine Issue: Page 660". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 124, 128.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (June 12, 2023). "Magazines 2". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 136, 159.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (June 15, 2023). "Romance/Romantic Range". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ Powers (2019), pp. 140, 159.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (June 15, 2023). "Detective Story Magazine". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ Weinberg (1985), pp. 183–185.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 249.

Sources[edit]

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-865-2.

- Bacon, Daisy (1954). Love Story Writer. New York: Hermitage House. OCLC 2941236.

- Hefner, Brooks E. (2021). Black Pulp: Genre Fiction in the Shadow of Jim Crow. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-6678-6.

- Murray, Will (2012). Writings in Bronze. Boston: Altus Press. ISBN 978-1-61827-045-0.

- Powers, Laurie (2019). Queen of the Pulps: The Reign of Daisy Bacon and Love Story Magazine. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-7396-7.

- Stone, Jon R. (2006). The Routledge Book of World Proverbs. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96895-6.

- Weinberg, Robert (1985). "Doc Savage". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 0-3132-1221-X.